Some time ago, I wrote an article called "Do This and You Will Win". In that post, I suggested performing interval training as follows: "ride absolutely as hard as you can for one minute, then soft pedal as easy as you can for three minutes, repeat 5-8 times or until you think you see Jesus." Assuming that the rider also raced on the weekends, these intervals would be done once a week.

Since writing that article, I have read numerous critiques of interval training, and heard talk from fellow racers about what they think is the best interval training method. This made me wonder what is the best interval training protocol or if there even is a best method. As I think back, I can not even remember exactly the source of my High-Intensity Interval Training (HIT) method. It certainly didn't come from Lemond's "Complete Book of Cycling." Nor did it come from Edward 'Eddie B' Borysewicz's "Bicycle Road Racing: The Complete Program for Training and Competition." And it definitely did not come from Joe Friel's "Cyclist's Training Bible" (though all are recommended books). My best guess is that I adopted my interval protocol from an article that I read in Bicycling Magazine, probably a couple decades ago, and it probably was written by Edmund Burke (who was well known for writing science-based training articles).

So my current question is two-fold. First, is my previously recommended method for improving cycling performance good advice? And second, are there other HIT protocols that are equal or better? Or to put it another way, is there an ultimate interval?

The importance of intervals

Interestingly, not only is adding a HIT program to your training necessary to reach your full cycling potential, but it can also dramatically speed up the rate at which fitness is achieved. It is generally believed that it can take several years to go from being an unfit to a highly fit bike racer; however research suggests otherwise. For example: Hickson showed that after just 10 weeks of HIT, VO2max could be rapidly increased (+44%; p<0.05) and four of his subjects approached or exceeded 60ml/kg/min in this short time frame. This does not mean that any cyclist can become an elite rider (>70ml/kg/min for men and >60 for women) in a very short period, though many can become "highly fit" (>60 ml/kg/min for men, >52 ml/kg/min for women) in a relatively short period of time. Fitness gains initially occur rapidly and depend on the volume, intensity and frequency of training; as greater fitness is achieved, it appears that the development of the physiological capacities witnessed in elite athletes does not continue to come about quickly. It may take years of high training loads before an individual reaches his or her full athletic potential through vascular and muscular adaptations. Outside of developing one's physiology, it can also take years to fully master the sport by developing racing and psychological skills (tactics, equipment, diet, technique, psychology, etc).

Another interesting and valuable fact about HIT is that, to a significant degree, when compared to aerobic (submaximal) training alone, it can reduce the exercise time required to achieve or maintain a particular level of fitness, as illustrated by Johnathan P. Little, and especially by Iaia FM, Hellsten Y, Nielsen JJ et al. In short, if you have limited time to exercise/train, then interval training is even more important and efficient for the gaining and maintaining fitness.

I have mentioned VO2max quite a few times in this article, so it is important to understand a few basics points about it. VO2max (also maximal oxygen consumption, maximal oxygen uptake, peak oxygen uptake or maximal aerobic capacity) reflects the physical fitness of the individual; it is the maximum capacity of an individual's body to transport and use oxygen during incremental exercise. While there certainly are other measures of fitness, maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) is widely accepted as the single best measure of cardiovascular fitness and maximal aerobic power. In this article, 60 ml/kg/min is used as the critical minimal threshold number for defining a "highly trained cyclist". For perspective and to see the full spectrum of comparative VO2 max measurements, classified from unfit (32 ml/kg/min) to world class cyclists (90 ml/kg/min) see my article "Comparative Measurements of Maximal Outputs for Cyclist".

There is a reason why I emphasize the distinction between "highly fit cyclists" (VO2max >60ml/kg/min) and lesser-fit cyclists (including sedentary individuals): research shows that "highly fit cyclists" do not respond to exercise stimuli in the same manner as unfit and moderately fit cyclists. Highly fit cyclists typically will not improve from further increased training volume (with enough volume they will actually get worse), whereas lower fit cyclists will almost always improve with increased training volume. Also, unfit and poorly fit cyclists can dramatically improve their fitness using nearly any HIT protocol, whereas highly fit cyclists not only exhibit considerably smaller gains, but in many cases they will not make any improvements at all with a HIT protocol that is not correctly designed for them (intensity level, repetitions, rest duration, and frequency).

Research findings from HIT studies

Below (Table One) are some findings from high intensity interval training studies in sedentary and recreationally-active individuals. (Source: Laursen & Jenkin's, "The Scientific Basis for High-Intensity Interval Training: Optimizing Training Programmes and Maximizing Performance in Highly Trained Endurance Athletes." ) The findings are organized by year of publication, and each study is referenced with links at the bottom of this article. Collectively, they show that lower fit riders respond well to a wide range of interval protocols - and importantly, many of these studies are the foundation for later research that looks for the best HIT protocols for highly fit cyclists. The general trend seen in these HIT protocols is to lower the work duration as the intensity is increased. The studies also increase the number of repetitions as the intensity level is lowered to a specific work duration. Rest between intervals tends to increase in proportion to the amount of work that is done as the intensity increases, and the total number of repetitions is typically determined by fatigue. Tabata's design is a bit of an exception to this trend with a 20 second work duration and a 10 second rest, but his protocol could be described as one 4 minute intermittent high intensity interval.

Surprises

One of the biggest surprise findings for early researchers (and for myself

while researching this topic) was that short 20-30 second HIT could

improve both VO2max and 40k time trial results. By training with short, intense intervals which use primary anaerobic energy (see figure 1 below) a person can achieve significant

improvements in long sustained efforts, which largely rely on aerobic energy such as 40 kilometer time trialing. This isn't exactly intuitive.

The Ultimate Interval

So, what is the ultimate interval? First we must ask what is it we are trying to enhance? As we can see from Figure 1 above, short intense events such as track racing require very high anaerobic capacities and endurance events such as 40k time trialing require very high aerobic capacities. However, for the purposes of this article, I avoid the topic of "sprinting" (5-15 maximal bursts) and focus on HIT for longer time frames that are commonly used in time trialing and criterium racing. (Sprint training could be discussed in a future article). With this in mind, I present a collection of findings from high-intensity interval training in highly trained cyclists, below in Table 2. These are currently the best and most cited studies that I could find on the topic. It is also important to reiterate that these studies are on highly trained cyclists; as mentioned previously, they respond to exercise stimuli differently than unfit and recreational cyclists.

So, which is the best? Let me quote one of the lead researchers, Paul Laursen,: "It is not possible to unequivocally state that one HIT group improved to a greater extent than the other HIT groups." ("Interval training program optimization in highly trained endurance cyclists"). However, he does go on to pick out the HIT protocol performed at the intensity of Pmax and a duration of Tmax with a 1:2 work-recovery ratio, as being superior by a small margin to the others. Ian Dille published an excellent article in Bicycling Magazine titled "The Ultimate Interval", in which he describes this particular HIT protocol in understandable terms. But to call this particular interval the ultimate interval is a little bit premature. It is extremely effective, but when we look at the last HIT study in table 2, in only 2 weeks, a group of higher fit cyclists (higher starting VO2max) improved nearly as much as the supposed ultimate interval group did in 4 weeks, while using dramatically different protocols. And CRITICALLY: the importance of sample size calculation cannot be overemphasized. The studies that I have cited all have extremely small sample sizes ranging from only 5 to 23 subjects, with most studies having fewer subjects than fingers on my hands. Size matters, and confidence in research findings goes up considerably with increased sample size, and down with smaller sample size because of variability between subjects (some test subjects may respond VERY different to protocols than others). Therefore, one should be very cautious to pick out one of the studies as definitely the best or ultimate over the others in my post.

So, what we see is that there are likely MANY different HIT protocol designs that are equally effective. The general rule for an ideal HIT protocol appears to be to lower the work duration as the intensity is increased, and to increase the number of repetitions as the intensity level is lowered to a specific work duration. Rest duration between intervals tends to increase in proportion to the amount of work that is done as intensity increases, and the total number of repetitions is typically determined by fatigue.

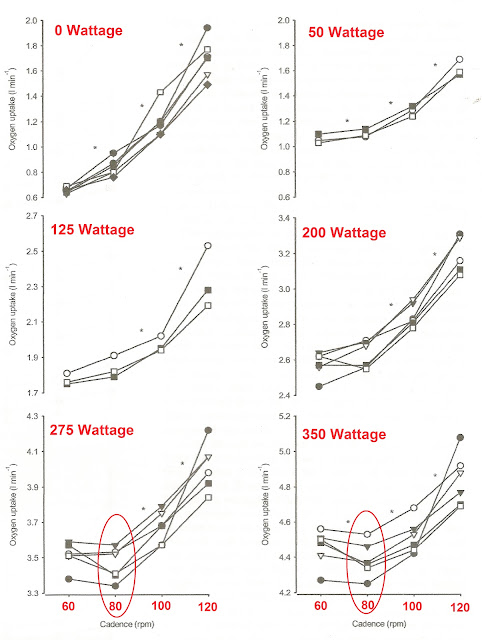

I would generally advise executing a HIT regimen based on research and not on intuition or hearsay. Any of those shown in table 2 are satisfactory. However, it can be difficult if not impossible to follow these protocols if a person does not have power meters and access to lab equipment for calculating precise PPO, Pmax and Tmax. Even if you have a power meter, it can be very hard. For example to determine PPO, you need to find your highest 30-second power output completed during an incremental test where resistance is increased by 15 watts every 30 seconds, starting at a workload of 100watts. Your Pmax is calculated by finding the corresponding power output that is measured at VO2max during a progressive exercise test, and Tmax is time to exhaustion at Pmax. Laursen deemed test subjects fully exhausted when they could not keep their cadence above 60 rpm. Sounds simple? No, it's not.

You may be able to estimate a PPO by testing yourself on a stationary trainer and using a powermeter device. After lightly warming up begin riding at 100 watts. Increase power by 30 watts every minute (you will have to control your wattage by cadence primarily) until you reach exhaustion (failure to maintain a 60 rpm cadence). Wattage at PPO is going to be higher than at Pmax by a small unknown amount. Pmax can only be determined accurately in a lab environment that can measure VO2max with it's corresponding watt output. However, you can estimate you Pmax by taking the average wattage produced over a 5 minute maximal effort and multiply that by .934 (based on writings from Andrew Coggan and only applies to highly fit cyclists).

Without a power meter you could just simply follow my simple "no tool" method (other than a watch). I can not unequivocally state that this protocol is as good as the proven studies below, but based on the principles of HIT it should produce comparably similar results. All you have to do is ride as hard as you can for one minute and rest three minutes or until you subjectively feel recovered and do it again and again until exhaustion or you see Jesus. When you see Jesus, that's when you know it's time to stop.

Training volume considerations with HIT

All of the highly trained cyclists in the studies cited maintained a high-volume low intensity (submaximal) training ranging from 285 kilometer plus minus 95 kilometers (177 miles plus minus 59 miles) per week, both before and during the study. In a review of HIT research Laursen (see 23 below) states that, "a polarized approach to training, whereby about 75% of total training volume is performed at low intensities, and 10-15% is performed at very high intensities, has been suggested as an optimal training intensity distribution for elite athletes who perform intense exercise events."

For cyclists who race every weekend, I would suggest doing only one interval session per week in order to avoid over-training and consider the weekend races collectively as a second interval. There are a number of bike racers who use racing to get themselves into shape. This is tried and true, but I speculate that controlled intervals, bi-weekly as described in Table 2 (below) may be superior. This may be because while racing will certainly produce stress that can trigger fitness, the efforts produced during a race may not be as completely exhausting as an ideal interval session or with the optimal amounts of intensity and work duration. And because racing has little to no rest opportunities, most cyclists are likely to race more strategically-minded than HIT-minded.

1. Hickson RC, Bomze HA, Holloszy JO. Linear increase in aerobic power induced by a strenuous program of endurance exercise

2. Henritze J, Weltman A, Schurrer RL, et al. Effects of training at and above the lactate threshold on the lactate threshold and maximal oxygen uptake

3. Simoneau JA, Lortie G, Boulay MR, et al. Human skeletal muscle fiber type alteration with high-intensity intermittent training

4. Simoneau JA, Lortie G, Boulay MR, et al. Effects of two high-intensity intermittent training programs interspaced by detraining on human skeletal muscle and performance

5. Green HJ, Fraser IG. Differential effects of exercise intensity on serum uric acid concentration

6. Nevill ME, Boobis LH, Brooks S, et al. Effect of training on muscle metabolism during treadmill sprinting

7. Keith SP, Jacobs I, McLellan TM. Adaptations to training at the individual anaerobic threshold

8. Linossier MT, Dennis C, Dormois D, et al. Ergometric and metabolic adaptation to a 5-s sprint interval training

9. Burke J, Thayer R, Belcamino M. Comparison of effects of two interval-training programmes on lactate and ventilatory thresholds

10. Lindsay FH, Hawley JA, Myburgh KH, et al. Improved athletic performance in highly trained cyclists after interval training

11. Tabata I, Mishimura K, Kouzaki M, et al. Effects of moderate intensity endurance and high-intensity intermittent training on anaerobic capacity

12. Westgarth-Taylor C, Hawley JA, Rickard S, et al. Metabolic and performance adaptations to interval training in endurance trained cyclists

13. MacDougall JD, Hicks AL, MacDonald JR, et al. Muscle performance and enzymatic adaptations to sprint interval training

14. Ray CA. Sympathetic adaptations to one-legged training

15. Green H, Tupling R, Roy B, et al. Adaptations in skeletal muscle exercise metabolism to a sustained session of heavy intermittent exercise

16. Rodas G, Ventura Jl, Dadefau JA, et al. A short training programme for the rapid improvement of both aerobic and anaerobic metabolism

17. Parra J, Cadefau JA, Rodas G, et al. The distribution of rest periods affects performance and adaptations of energy metabolism induced by high-intensity training in human muscle

18. Harmer AR, McKenna MJ, Sutton JR, et al. Skeletal muscle metabolic and ionic adaptations during intense exercise following sprint training in humans

19. Laursen PB, Shing CM, Peake JM, et al. Interval training program optimization in highly trained endurance cyclists

20. Laursen PB, Blanchard MA, Jenkins DG Acute high-intensity interval training improves Tvent and peak power output in highly trained males

21. Laursen PB, Shing CM, Peake JM, et al. Influence of high-intensity interval training on adaptations in well-trained cyclists

22. Spencer MR, Gastin PB Energy system contribution during 200- to 1500- m running in highly trained athletes

23. Laursen PB Training for intense exercise performance: high-intensity or high-volume training?

Since writing that article, I have read numerous critiques of interval training, and heard talk from fellow racers about what they think is the best interval training method. This made me wonder what is the best interval training protocol or if there even is a best method. As I think back, I can not even remember exactly the source of my High-Intensity Interval Training (HIT) method. It certainly didn't come from Lemond's "Complete Book of Cycling." Nor did it come from Edward 'Eddie B' Borysewicz's "Bicycle Road Racing: The Complete Program for Training and Competition." And it definitely did not come from Joe Friel's "Cyclist's Training Bible" (though all are recommended books). My best guess is that I adopted my interval protocol from an article that I read in Bicycling Magazine, probably a couple decades ago, and it probably was written by Edmund Burke (who was well known for writing science-based training articles).

So my current question is two-fold. First, is my previously recommended method for improving cycling performance good advice? And second, are there other HIT protocols that are equal or better? Or to put it another way, is there an ultimate interval?

The importance of intervals

Before I go straight to the answer, I should first explain the importance of HIT, and why it has value. It is well established among exercise physiologists and others, that any amount of exercise followed by recovery will increase fitness for sedentary (unfit) individuals. For beginner and moderately-trained cyclists, increased duration and increased frequency of riding combined with recovery is all that is required to further increase fitness. Unfortunately, this method of increasing fitness has a ceiling and once this threshold is reached, no amount of increased typical or ordinary riding (aka sub-maximal exercise or below threshold markers) will continue to improve a rider's fitness. As Laursen & Jenkins state, "in the highly trained athlete, an additional increase in sub-maximal exercise training (i.e. volume) does not appear to further enhance either endurance performance or associated variables such as maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max), anaerobic threshold, economy of motion and oxidative muscle enzymes". In citing Ben Londeree's research, the authors note that "it appears that once an individual has reached a VO2max >60ml/kg/min, endurance performance is not improved by a further increase in submaximal training volume." This is not meant to downplay the importance of high-volume training, but to highlight that there is a fixed limit for improving fitness by this method alone.

Interestingly, not only is adding a HIT program to your training necessary to reach your full cycling potential, but it can also dramatically speed up the rate at which fitness is achieved. It is generally believed that it can take several years to go from being an unfit to a highly fit bike racer; however research suggests otherwise. For example: Hickson showed that after just 10 weeks of HIT, VO2max could be rapidly increased (+44%; p<0.05) and four of his subjects approached or exceeded 60ml/kg/min in this short time frame. This does not mean that any cyclist can become an elite rider (>70ml/kg/min for men and >60 for women) in a very short period, though many can become "highly fit" (>60 ml/kg/min for men, >52 ml/kg/min for women) in a relatively short period of time. Fitness gains initially occur rapidly and depend on the volume, intensity and frequency of training; as greater fitness is achieved, it appears that the development of the physiological capacities witnessed in elite athletes does not continue to come about quickly. It may take years of high training loads before an individual reaches his or her full athletic potential through vascular and muscular adaptations. Outside of developing one's physiology, it can also take years to fully master the sport by developing racing and psychological skills (tactics, equipment, diet, technique, psychology, etc).

Another interesting and valuable fact about HIT is that, to a significant degree, when compared to aerobic (submaximal) training alone, it can reduce the exercise time required to achieve or maintain a particular level of fitness, as illustrated by Johnathan P. Little, and especially by Iaia FM, Hellsten Y, Nielsen JJ et al. In short, if you have limited time to exercise/train, then interval training is even more important and efficient for the gaining and maintaining fitness.

I have mentioned VO2max quite a few times in this article, so it is important to understand a few basics points about it. VO2max (also maximal oxygen consumption, maximal oxygen uptake, peak oxygen uptake or maximal aerobic capacity) reflects the physical fitness of the individual; it is the maximum capacity of an individual's body to transport and use oxygen during incremental exercise. While there certainly are other measures of fitness, maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) is widely accepted as the single best measure of cardiovascular fitness and maximal aerobic power. In this article, 60 ml/kg/min is used as the critical minimal threshold number for defining a "highly trained cyclist". For perspective and to see the full spectrum of comparative VO2 max measurements, classified from unfit (32 ml/kg/min) to world class cyclists (90 ml/kg/min) see my article "Comparative Measurements of Maximal Outputs for Cyclist".

There is a reason why I emphasize the distinction between "highly fit cyclists" (VO2max >60ml/kg/min) and lesser-fit cyclists (including sedentary individuals): research shows that "highly fit cyclists" do not respond to exercise stimuli in the same manner as unfit and moderately fit cyclists. Highly fit cyclists typically will not improve from further increased training volume (with enough volume they will actually get worse), whereas lower fit cyclists will almost always improve with increased training volume. Also, unfit and poorly fit cyclists can dramatically improve their fitness using nearly any HIT protocol, whereas highly fit cyclists not only exhibit considerably smaller gains, but in many cases they will not make any improvements at all with a HIT protocol that is not correctly designed for them (intensity level, repetitions, rest duration, and frequency).

Research findings from HIT studies

Below (Table One) are some findings from high intensity interval training studies in sedentary and recreationally-active individuals. (Source: Laursen & Jenkin's, "The Scientific Basis for High-Intensity Interval Training: Optimizing Training Programmes and Maximizing Performance in Highly Trained Endurance Athletes." ) The findings are organized by year of publication, and each study is referenced with links at the bottom of this article. Collectively, they show that lower fit riders respond well to a wide range of interval protocols - and importantly, many of these studies are the foundation for later research that looks for the best HIT protocols for highly fit cyclists. The general trend seen in these HIT protocols is to lower the work duration as the intensity is increased. The studies also increase the number of repetitions as the intensity level is lowered to a specific work duration. Rest between intervals tends to increase in proportion to the amount of work that is done as the intensity increases, and the total number of repetitions is typically determined by fatigue. Tabata's design is a bit of an exception to this trend with a 20 second work duration and a 10 second rest, but his protocol could be described as one 4 minute intermittent high intensity interval.

|

| key to the abbreviations used in the charts |

The Ultimate Interval

So, what is the ultimate interval? First we must ask what is it we are trying to enhance? As we can see from Figure 1 above, short intense events such as track racing require very high anaerobic capacities and endurance events such as 40k time trialing require very high aerobic capacities. However, for the purposes of this article, I avoid the topic of "sprinting" (5-15 maximal bursts) and focus on HIT for longer time frames that are commonly used in time trialing and criterium racing. (Sprint training could be discussed in a future article). With this in mind, I present a collection of findings from high-intensity interval training in highly trained cyclists, below in Table 2. These are currently the best and most cited studies that I could find on the topic. It is also important to reiterate that these studies are on highly trained cyclists; as mentioned previously, they respond to exercise stimuli differently than unfit and recreational cyclists.

So, which is the best? Let me quote one of the lead researchers, Paul Laursen,: "It is not possible to unequivocally state that one HIT group improved to a greater extent than the other HIT groups." ("Interval training program optimization in highly trained endurance cyclists"). However, he does go on to pick out the HIT protocol performed at the intensity of Pmax and a duration of Tmax with a 1:2 work-recovery ratio, as being superior by a small margin to the others. Ian Dille published an excellent article in Bicycling Magazine titled "The Ultimate Interval", in which he describes this particular HIT protocol in understandable terms. But to call this particular interval the ultimate interval is a little bit premature. It is extremely effective, but when we look at the last HIT study in table 2, in only 2 weeks, a group of higher fit cyclists (higher starting VO2max) improved nearly as much as the supposed ultimate interval group did in 4 weeks, while using dramatically different protocols. And CRITICALLY: the importance of sample size calculation cannot be overemphasized. The studies that I have cited all have extremely small sample sizes ranging from only 5 to 23 subjects, with most studies having fewer subjects than fingers on my hands. Size matters, and confidence in research findings goes up considerably with increased sample size, and down with smaller sample size because of variability between subjects (some test subjects may respond VERY different to protocols than others). Therefore, one should be very cautious to pick out one of the studies as definitely the best or ultimate over the others in my post.

So, what we see is that there are likely MANY different HIT protocol designs that are equally effective. The general rule for an ideal HIT protocol appears to be to lower the work duration as the intensity is increased, and to increase the number of repetitions as the intensity level is lowered to a specific work duration. Rest duration between intervals tends to increase in proportion to the amount of work that is done as intensity increases, and the total number of repetitions is typically determined by fatigue.

HIT applied in the real world

I would generally advise executing a HIT regimen based on research and not on intuition or hearsay. Any of those shown in table 2 are satisfactory. However, it can be difficult if not impossible to follow these protocols if a person does not have power meters and access to lab equipment for calculating precise PPO, Pmax and Tmax. Even if you have a power meter, it can be very hard. For example to determine PPO, you need to find your highest 30-second power output completed during an incremental test where resistance is increased by 15 watts every 30 seconds, starting at a workload of 100watts. Your Pmax is calculated by finding the corresponding power output that is measured at VO2max during a progressive exercise test, and Tmax is time to exhaustion at Pmax. Laursen deemed test subjects fully exhausted when they could not keep their cadence above 60 rpm. Sounds simple? No, it's not.

You may be able to estimate a PPO by testing yourself on a stationary trainer and using a powermeter device. After lightly warming up begin riding at 100 watts. Increase power by 30 watts every minute (you will have to control your wattage by cadence primarily) until you reach exhaustion (failure to maintain a 60 rpm cadence). Wattage at PPO is going to be higher than at Pmax by a small unknown amount. Pmax can only be determined accurately in a lab environment that can measure VO2max with it's corresponding watt output. However, you can estimate you Pmax by taking the average wattage produced over a 5 minute maximal effort and multiply that by .934 (based on writings from Andrew Coggan and only applies to highly fit cyclists).

Without a power meter you could just simply follow my simple "no tool" method (other than a watch). I can not unequivocally state that this protocol is as good as the proven studies below, but based on the principles of HIT it should produce comparably similar results. All you have to do is ride as hard as you can for one minute and rest three minutes or until you subjectively feel recovered and do it again and again until exhaustion or you see Jesus. When you see Jesus, that's when you know it's time to stop.

Training volume considerations with HIT

All of the highly trained cyclists in the studies cited maintained a high-volume low intensity (submaximal) training ranging from 285 kilometer plus minus 95 kilometers (177 miles plus minus 59 miles) per week, both before and during the study. In a review of HIT research Laursen (see 23 below) states that, "a polarized approach to training, whereby about 75% of total training volume is performed at low intensities, and 10-15% is performed at very high intensities, has been suggested as an optimal training intensity distribution for elite athletes who perform intense exercise events."

For cyclists who race every weekend, I would suggest doing only one interval session per week in order to avoid over-training and consider the weekend races collectively as a second interval. There are a number of bike racers who use racing to get themselves into shape. This is tried and true, but I speculate that controlled intervals, bi-weekly as described in Table 2 (below) may be superior. This may be because while racing will certainly produce stress that can trigger fitness, the efforts produced during a race may not be as completely exhausting as an ideal interval session or with the optimal amounts of intensity and work duration. And because racing has little to no rest opportunities, most cyclists are likely to race more strategically-minded than HIT-minded.

1. Hickson RC, Bomze HA, Holloszy JO. Linear increase in aerobic power induced by a strenuous program of endurance exercise

2. Henritze J, Weltman A, Schurrer RL, et al. Effects of training at and above the lactate threshold on the lactate threshold and maximal oxygen uptake

3. Simoneau JA, Lortie G, Boulay MR, et al. Human skeletal muscle fiber type alteration with high-intensity intermittent training

4. Simoneau JA, Lortie G, Boulay MR, et al. Effects of two high-intensity intermittent training programs interspaced by detraining on human skeletal muscle and performance

5. Green HJ, Fraser IG. Differential effects of exercise intensity on serum uric acid concentration

6. Nevill ME, Boobis LH, Brooks S, et al. Effect of training on muscle metabolism during treadmill sprinting

7. Keith SP, Jacobs I, McLellan TM. Adaptations to training at the individual anaerobic threshold

8. Linossier MT, Dennis C, Dormois D, et al. Ergometric and metabolic adaptation to a 5-s sprint interval training

9. Burke J, Thayer R, Belcamino M. Comparison of effects of two interval-training programmes on lactate and ventilatory thresholds

10. Lindsay FH, Hawley JA, Myburgh KH, et al. Improved athletic performance in highly trained cyclists after interval training

11. Tabata I, Mishimura K, Kouzaki M, et al. Effects of moderate intensity endurance and high-intensity intermittent training on anaerobic capacity

12. Westgarth-Taylor C, Hawley JA, Rickard S, et al. Metabolic and performance adaptations to interval training in endurance trained cyclists

13. MacDougall JD, Hicks AL, MacDonald JR, et al. Muscle performance and enzymatic adaptations to sprint interval training

14. Ray CA. Sympathetic adaptations to one-legged training

15. Green H, Tupling R, Roy B, et al. Adaptations in skeletal muscle exercise metabolism to a sustained session of heavy intermittent exercise

16. Rodas G, Ventura Jl, Dadefau JA, et al. A short training programme for the rapid improvement of both aerobic and anaerobic metabolism

17. Parra J, Cadefau JA, Rodas G, et al. The distribution of rest periods affects performance and adaptations of energy metabolism induced by high-intensity training in human muscle

18. Harmer AR, McKenna MJ, Sutton JR, et al. Skeletal muscle metabolic and ionic adaptations during intense exercise following sprint training in humans

19. Laursen PB, Shing CM, Peake JM, et al. Interval training program optimization in highly trained endurance cyclists

20. Laursen PB, Blanchard MA, Jenkins DG Acute high-intensity interval training improves Tvent and peak power output in highly trained males

21. Laursen PB, Shing CM, Peake JM, et al. Influence of high-intensity interval training on adaptations in well-trained cyclists

22. Spencer MR, Gastin PB Energy system contribution during 200- to 1500- m running in highly trained athletes

23. Laursen PB Training for intense exercise performance: high-intensity or high-volume training?